The traffic over this road during the months of June, July, August, September, and October, 1914, consisted of the movement of one mixed train, Cordova to Kennecott and return, scheduled to leave at intervals of five or six days, meeting the Alaska Steamship Co.’s boats northbound from Seattle. At infrequent intervals specials were operated for some particular purpose, and the train service was further supplemented by passenger motor car as occasion demanded. This service was increased in November.The 1913 Alaska Railroad Commission report shows a somewhat different picture:

Three through trains a week are operated between Chitina and Cordova, in addition to a daily freight train from the Kennicott branch.The overall impression from both of these reports strikes me as somewhat garbled. I think it's generally recognized that the only significant freight traffic source on the CR&NW was the Kennicott mill.

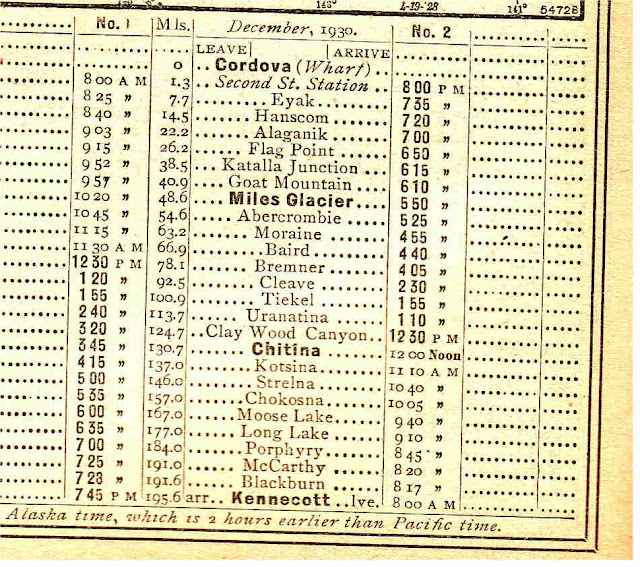

A schedule that appears to be in the Official Guide from 1930 shows a daily train, likely a mixed, between Cordova and Kennicott that took 12 hours for the run.

This would have been interrupted frequently due to snow and washouts, especially of the Copper River crossing at Chitina. For two years in the 1930s, the line did not operate at all, and afterward, it did not operate in the winter.

The statistics in the Wikipedia entry on Kennicott give an idea of how much this traffic was over the years: "In the 27 years of operation, except for 2½ years of shutdown, Kennecott produced 4.625 million tons of ore[.]"

So 25 years of production is 9125 days. During peak years, the mines operated seven days per week, all year. 4.625 million tons divided by 9125 days gives about 508 tons per day. So averaged over all the years of production, leaving out 1933-35 when the mines closed and the railroad shut down, the traffic amounted to about ten 50-ton capacity cars of ore per day. (Since the ore traveled mainly in sacks on steel flat cars, I'm assuming these were 50 ton capacity.)

This suggests that, on average, the daily freight from Kennicott to Cordova mentioned in the 1913 report would have had ten cars. In later years, with the line shut in the winter and the mines producing at a lower level, the freights would have run less than once per day. The peak years for the mines and the railroad were about 1916-1925, when the freights would probably have been longer, but quite possibly not more often than once per day.

So trying to make some sense of the conflicting reports from 1913 and 1915, it sounds as if during peak years, there was a mixed train, possibly from Cordova to Chitina, three times a week. A daily freight ran from Kennicott to Cordova and return. Passenger specials ran as "cruise train" excursions coordinated with steamship arrivals. Other passenger moves were via Model T speeders as needed. After about 1930, operations would have been less, probably combining the mixed trains with the Kennicott freights.

Considering the manual unloading process for the ore sacks at Cordova, it seems unlikely that facilities there could have handled much more than 10-20 cars per day at any time. I would guess that the need to shift cars on the wharf for unloading in years of peak production might have required a switcher in Cordova, presumably one of the lighter locos.

On top of that, there would have been a need to operate rotary outfits during the winter months. Other work extras to fill sinking trackage in the Baird Glacier area and clear rockslides in Abercrombie Canyon would also have been needed with some frequency.

.jpg)

.jpg)